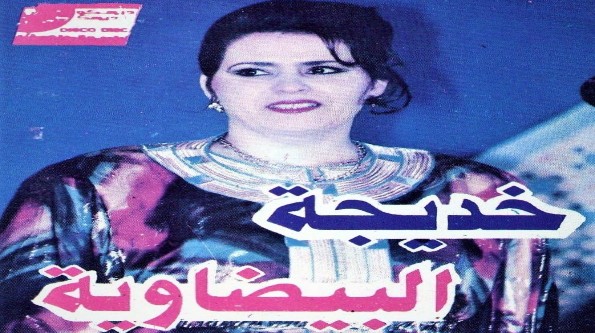

Khadija el Bidawiya was born in 1953, in Ben Msik Sbata, the densely populated and chronically marginalized neighborhood on the southeastern fringe of Casablanca that has long been an incubator of al-aita, the popular music of Morocco’s Arabic speaking rural and urban poor. (The neighborhood has also sent more players than any other to Casablanca’s two greatest soccer clubs, the Raja and the Wydad.) Khadija grew up, in a conservative and modest family, to the music of Bouchaib Bidaoui, a star of Moroccan popular theater and one of the kingdom’s first television and recording stars. A gifted singer, Khadija learned the rudiments of her art memorizing Bouchaib’s repertoire, and imitating the singers she heard at neighborhood weddings. She was forced, however, to put aside her creative ambitions when she got married; her husband wouldn’t allow her to even attend musical events. It wasn’t until 1979, when she was in her mid twenties, and husband had passed away, that Khadija started to perform in public. She made her public debut, unbeknownst to her family, as a dancer accompanying a popular Cheikhate—a female singer—from the neighborhood.

When we spoke, Khadija reminisced, “I would tell my family that I was spending the night at an aunt’s house, and I would go perform at weddings with a group of Cheikhates. I was a very popular dancer. But even though I was showered with money every evening, I would be in tears at the end of each performance. I was ashamed. My family had always told me that singing and dancing in public was shameful. Finally, one night, my boss told me, ‘you have to accept your talent. You are an artist.’ A few weeks later, I admitted to one of my aunt’s that I was performing.” By the end of 1979, Khadija was singing on stage, winning over fans with her strident voice.

Ten years later, Khadija had her own group, released over a dozen cassettes, and was recognized as the rising queen of al-Aita Marsaouiya. According to Hassan Najmi, author of the two volume Al-Aita:Oral Poetry and Traditional Music in Morocco (in Arabic), al-aita is the oldest style of Arabic language music in Morocco, with some songs dating back to the 12th century. Al-Aita songs have their roots in the poetry of the Beni Hillal, the tribes from the Arabian Peninsula who started to settle in present-day Morocco in the 11th century. Najmi identifies nine distinct regional varieties of al-aita, the youngest, and today most dominant, being al-aita marsaouiya. For centuries, al-aita was the music of village festivities, marriages, and harvest celebrations, performed by amateur musicians. The songs expressed the values, hopes, frustrations and tribal identities of Morocco’s rural Arabic speaking—as opposed to Berber speaking—communities.

The story of al-aita marsaouiya is the story of Casablanca and of rural migration to the big city. Starting in the late 19th century, and picking up dramatically in the 1930s when the surrounding regions suffered serious droughts (1936, 1937, 1939 and1945), poor farmers made their way to the ‘marsa’—the market or port—of Casablanca to find wage labor. These rural migrants settled in dense and disorganized neighborhoods like Ben Msik Sbata, where along with their dreams of a more stable and prosperous life, they brought their songs and poems. It was in this overcrowded suburb of Casablanca that the first generation of professional Cheikhs and Cheikhates started to earn a living performing al-aita marsaouiya. This group of Marsaoui pioneers include the aforementioned Bouchaib Bidaoui, who dominated the city’s café scene, Fatma Bent el Houcine (perhaps the greatest Cheikha of the modern era), and Hajja Hamdaouia—who came to music, under Bidaoui’s tutelage, through the popular theater and who is still performing today.

When I asked Khadija al Bidawiya about the history of al-aita, she told me the story of Kharboucha: “There was a Caid by the name of Si Aissa ben Omar elAbdi who ruled despotically over the Ouled Zaid tribe, helping himself to all of the tribe’s resources and riches, including their most attractive daughters. One day, this Caid decided that he wanted Kharboucha for his wife. He asked for her hand in marriage but Kharboucha refused. She had already given her heart to another, the Caid Si Aissa’s son. If Kharboucha would not marry him, the Caid decided, she would never marry. Her punishment was brutal. Kharboucha was buried alive. But as she was being walled into her tomb, Kharboucha defied the Caid, singing a long poem that divulged her love for his son.” There are several different versions of the legend of Kharboucha—historians believe her real name was Hadda, and that she was a popular early twentieth century aita singer from the town of Safi—and her boldness continues to inspire Moroccan poets, playwrights, filmmakers, and singers. Kharboucha’s story incarnates the main themes of aita songs; determined pride, unrequited longing, the injustice of life, and the obduracy of true love.

Khadija al Bidawiya has lost count of the number of cassettes she has recorded. At her creative peak in the late 1990s Khadija was releasing four to six cassettes a year, and today, she releases a cassette every six months. Khadija has performed for Moroccan audiences in France, Belgium, and the Netherlands, and over last decade has settled into her reputation as the doyenne of al-aita marsaouiya.

Voanews 2011